The Red Ball Express was a famous truck convoy system that supplied Allied forces moving quickly through Europe after breaking out from the D-Day beaches in Normandy in 1944. To expedite cargo shipment to the front, trucks emblazoned with bright red circles attached to the grille followed a marked route that was closed to civilian traffic. These trucks also had priority on regular roads.

The Goodyear Wingfoot Express fleet’s design and extensive trips were completed with one purpose in mind — to convince shippers and truckers that trucks on pneumatic tires need no longer be limited to local hauls. At the time, truckers didn’t believe long hauls were practical and refused to give the new air-filled tires a reasonable try.

It wasn’t an easy task. On April 9, 1917, drivers Harry Apple and Harry Smeltzer climbed aboard a five-ton Packard truck with pneumatic tires and headed east. Their cargo wasn’t a payload on that first run. Instead, they carried a dozen spare tires, an air compressor, 500 feet of rope, a heavy block and tackle, extra gas, oil, and water. They needed them all and more.

Accompanying the Packard was a photographer, a public relations man, three engineers, and a shop foreman. Barely outside of Akron, the truck became mired in mud. From there on, the crew experienced broken bridges, two engine failures, a blowout every 75 miles, and other sundry problems.

Walter Shively, the tire engineer, promptly applied the lessons learned and frantic hours were spent redesigning and improving the tires. Stronger beads and heavier side walls greatly reduced the blowout problem. Within the year seven trucks were making the Akron-New England trip with a running time of 80 hours.

In 1918, at the request of the American Red Cross, the trucks were sent to Chicago to transport 18 tons of badly needed medical supplies to Baltimore Harbor, destined for France. That run took just 100 hours.

But the biggest challenge was yet to come. In the fall of 1918, the caravan completed the first of four 7,763-mile round trips from Boston to San Francisco. There isn’t a record of how long that first trip took, but by the time the last trip was completed there was a new transcontinental record of just 14 days from coast to coast.

The Goodyear Wingfoot Express is a true milestone of the trucking industry.

In 1938, the forerunner of Thermo King Corp. built its first mechanical refrigeration unit for a trailer. The three men who made trailer refrigeration possible were Joseph Numero, a lawyer turned entrepreneur who owned a movie theater; M.B. Green, a business school graduate who formed a quasi-partnership with Numero; and Frederick McKinley Jones, a self-taught African American handyman who worked for Numero at the movie theater.

The story of how the first refrigeration unit was born is an industry classic. One sultry summer afternoon Numero was playing golf with Harry Werner, founder of Werner Transportation Co., and an unnamed air conditioner “expert.” Werner was called to the phone to hear that one of his rigs had broken down and 10 tons of perishable food had to be thrown away.

Exasperated, he turned to the air conditioning man and said, “If you can cool a whole theater, why can’t you cool my trailers?” The expert gave a hundred reasons why it couldn’t be done. But, on impulse, Numero blurted, “We’ll build you a unit … in 30 days!”

Back at the theater, Numero challenged Jones to the task, and the handyman-turned-engineer immediately went into action. He obtained a 4-cylinder Waukesha engine, picked up components here and there, scoured junkyards for needed parts, and put them all together in a huge package. It was clumsy, cumbersome, weighed 2,800 lbs, and was mounted under the trailer with a lot of external plumbing. But it worked, at least when the trailer was standing still. On the road, however, dirt clogged the system and jammed the controls.

Jones went back to his shop, shaved off 400 lbs, made numerous improvements, and the Thermo King Model A went to market. Yet all agreed that a better location was needed. Next came the nose-mounted self-contained version, and the rest of the story is history. Vast improvements followed, including diesel or propane power, sophisticated controls, and the ability to heat as well as cool. Within a few years it opened vast new opportunities for long haul trucking and boosted the fledgling frozen food industry to a prominent place on the nation’s dining room tables.

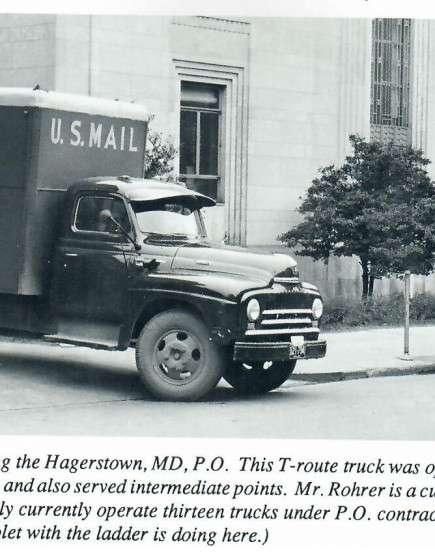

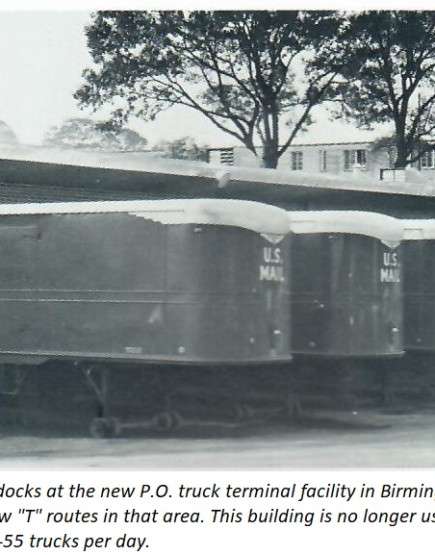

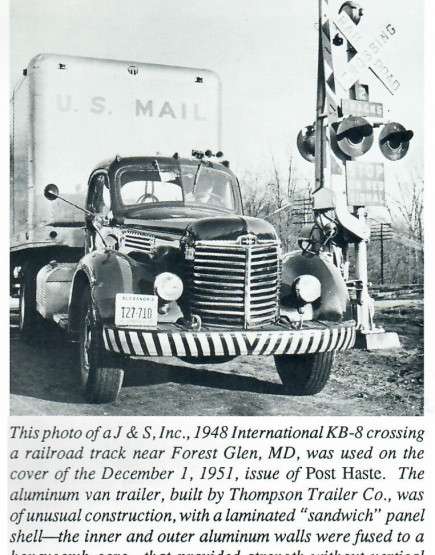

The first truck mail route had been established on August 17, 1948. The first “short haul” truck route, or “T” route, was operated by J&S, Inc. between Washington D.C. and Fredericksburg, VA, beginning March 1951. The first facility built specifically for trucks by the U.S. Post Office Bureau of Transportation was opened for business in 1951. Fredericksburg was being set up as a “Sectional Center,” a central point into which truck routes from a number of cities in a 100 mile radius converged, and where the incoming mail would be quickly sorted and reloaded onto the respective trucks to return to their points of origin.

Diverting short-haul mail traffic to trucks from railroads not only sped up delivery, reduced damage, and saved a considerable amount of money, but it also financed a large number of small contractors and provided for the expansion of existing truck lines. In 1951, the Post Office was the largest truck operator in the U.S. with more than 50,000 government owned or contracted units under the department’s supervision.

This system of competitive bid contracts is still expanding and saving the Postal Service millions of dollars each year. They are now called “HRC” contracts, for Highway Carrier Routes.